Elizabeth Bennet may not have burned corsets, but in a world where marriage was the only ladder up, she chose love on her own terms. Let’s unpack the quietly rebellious feminism in Pride and Prejudice.

Ah, the Regency era — where men inherited estates, women inherited embroidery hoops, and marrying well was considered the peak of feminine ambition. But in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, we meet Elizabeth Bennet — witty, stubborn, and delightfully unimpressed by pompous men in waistcoats. If the patriarchy was a ballroom, Lizzy would be the one pointedly sipping her punch in the corner, muttering clever retorts under her breath.

While not a modern-day feminist manifesto, Pride and Prejudice offers a quietly radical take on gender roles for its time — think of it as feminist subtext wearing an empire-line dress.

Marriage: Economic Strategy or Emotional Equity?

Let’s start with marriage — the ultimate career move for Regency women. As Charlotte Lucas pragmatically puts it, “I’m not romantic, you know. I never was. I ask only a comfortable home.” Translation: a roof over your head beats dying a spinster on your father’s land.

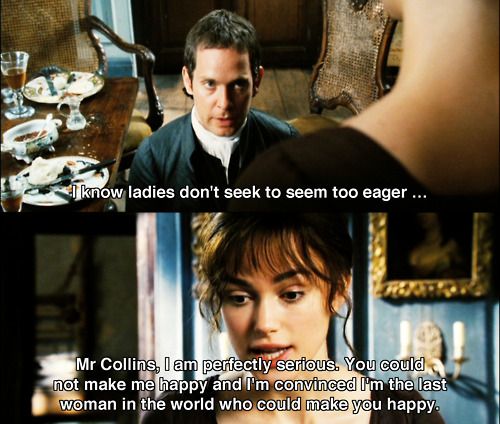

But not Elizabeth. She turns down Mr. Collins (and later Darcy’s first very unsmooth proposal) because she wants more than financial security — she wants respect, affection, and intellectual equality. In a world where women had few legal rights and even fewer economic options, her insistence on marrying for love is quietly revolutionary.

Feminine Intelligence: More Than Needlework

In a society where female education meant being “accomplished” — i.e., playing pianoforte and sketching fruit bowls — Elizabeth wields her intellect like a rapier. Her sharp observations challenge both social norms and the expectations placed on women to be agreeable above all else. Austen herself was a master of this: her narrative voice is dripping with irony, subtly critiquing the gendered power dynamics of the time while still playing by the rules.

Independence & Reputation

Elizabeth walks alone, reads voraciously, and speaks her mind. These actions — seemingly minor today — pushed the boundaries of “acceptable” feminine behaviour in the 1800s. Reputation was everything. One false step (like, say, your sister eloping with a shady soldier) and your entire family’s social standing could collapse. And yet, Elizabeth risks being labelled difficult, impertinent, even unmarriageable — all in the name of staying true to herself.

Austen’s Quiet Rebellion

Jane Austen didn’t burn bras (which didn’t exist yet) or march in the streets — but through her heroines, she offered a blueprint for challenging the system from within. Her sharp social commentary, delivered with grace and wit, reveals the cracks in the patriarchal façade.

Elizabeth Bennet isn’t a sword-wielding rebel — but her refusal to settle, her loyalty to her family, her thirst for knowledge, and her demand to be treated as an equal make her a feminist icon in petticoats.

Pride and Prejudice reminds us that feminism doesn’t always come in the form of loud declarations or grand gestures. Sometimes, it’s found in a woman refusing a proposal, reading a book instead of playing the piano, or daring to believe that she deserves love and respect.

So next time someone says Austen’s just about pretty dresses and romantic tension, hand them your copy and say, “It is a truth universally acknowledged… that this woman was way ahead of her time.”